Photo: Walidah Imarisha

BY DEBORAH MOON

“We have survived and thrived in a place that actively tried to exclude and expel us,” said activist and author Walidah Imarisha in the first of a series of webinars on Oregon's history of discrimination. (See series details below.)

“Uncovering the Hidden History of Anti-Black Racism in Oregon” was a condensed version of the program that the Portland State University assistant professor has presented across the state: “Why Aren’t There More Black People in Oregon? A Hidden History.”

Imarisha highlighted not only the history of oppression, but the resistance of Black and other oppressed communities. “Black communities have never been passive victims, they are active changemakers.”

The Oregon Territory, which encompassed the entire Northwest, passed two Black exclusion laws – one in 1844 and one in 1849 – that forbade Blacks from living in the territory. When Oregon became a state in 1859, it not only prohibited slavery, it also banned all Blacks from the state.

The goal of the white colonizers and those laws was to build a racist, white utopia, says Imarisha.

While many of Oregon’s Black exclusion laws were repealed or ruled unconstitutional by the middle of the 20th century, much of the language was left in place until very recently. For instance, the State Constitution clause that prohibited Blacks from being in the state, owning property and making contracts was repealed in 1926, but the language was not removed from the constitution until 2002.

“That was not an oversight,” says Imarisha. She adds that many homeowners’ association covenants still contain unenforced covenants that ban Blacks from owning homes in their neighborhood.

Oregon’s white supremacist history continued with the arrival of the Ku Klux Klan in 1921, the German-American (pro-Nazi) Bund in the 1930s and Portland’s reputation as the skinhead capital in the 1980s. The strong KKK presence had been deeply connected to community leaders and government officials with KKK member Walter Pierce elected Oregon governor in 1922.

“The fact that Black communities exist at all in Oregon is incredible,” she says.

Imarisha shared numerous examples of Black resistance that has made that possible:

• The 1860 census counted 124 Black residents, an example of courage and determination.

• In 1867 Black organizers worked with state and local government leaders to open public schools for Blacks. Oregon’s compulsory education law that banned private schools had kept many minorities from receiving an education since they were not accepted in public schools. Imarisha called the Black organizers courageous since they had no legal standing in Oregon. “They brought in public education for all.”

• In the 1920s, the NAACP led protests against screening “The Birth of a Nation,” which has been called the most racist film in U.S. history. In response, the Portland city council banned “any film that would stir up racial hatred.”

• As an example of cultural resistance, she noted Portland became known as a jazz treasure nationally from the 1930s to ‘50s – a time when Portland was America’s most segregated city outside of the South.

Imarisha says Portland has been adept at using progressive, liberal language “while allowing systems of oppression to continue.”

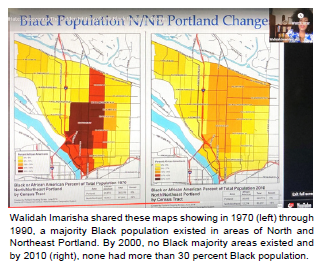

She points to gentrification as an example. Portland is both the most gentrified city and the whitest major city in the country. Majority Black communities in North and Northeast Portland grew through the 1970s and up until 1990. Then in a major demographic shift, in just 10 years there were no longer any communities with a majority Black population. Imarisha says, “Black folks were pushed east into Gresham, north to Vancouver, Wash. – out of the state – and into prisons.”

She points to gentrification as an example. Portland is both the most gentrified city and the whitest major city in the country. Majority Black communities in North and Northeast Portland grew through the 1970s and up until 1990. Then in a major demographic shift, in just 10 years there were no longer any communities with a majority Black population. Imarisha says, “Black folks were pushed east into Gresham, north to Vancouver, Wash. – out of the state – and into prisons.”

“It is important to recognize … gentrification works in tandem with brutal over-policing of communities,” says Imarisha. She adds that Oregon’s 1983 Measure 11 setting mandatory sentencing “was responsible for the huge explosion of the prison population that disproportionately affects Black people.”

Imarisha urges white allies and white accomplices to seek out the Black organizers and Black resistance leaders. “White folks need to research the organizing work of communities of color.”

“Black resistance … has happened continually using a diversity of tactics and strategies to create racial justice, which is essential for justice to exist.”

UNCOVERING THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION IN OREGON

A series focused on the history of hate in Oregon

Sponsored by the Jewish Federation’s Jewish Community Relations Council, the Portland Chapter of the NAACP, Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, and several other community groups.

“This hidden history has been ignored and whitewashed in our society and schools,” says JFGP Community Relations Director Bob Horenstein. He says the series will “help us understand how we got to this time where we still face serious racial injustice and serious discrimination.”

Videos of webinars will be posted as they occur. The first two programs – “Uncovering the Hidden History of Anti-Black Racism in Oregon” and “Healing and Reconciliation: The Hidden History of Anti-Native American Discrimination in Oregon” – are posted at the bottom of Federation’s Uncovering the Hidden History page jewishportland.org/uncovering.

Upcoming webinars:

Dec. 3: Latinx, immigrant discrimination

Jan. 21: LGBTQ discrimination

February: Asian discrimination (tentative)

March: Anti-Semitism

Summit on Confronting Hate

Whether online or in-person, the May Summit will discuss resources and strategies for historically oppressed communities to stand together in solidarity and confront hate.

Donate to Black Resilience Fund on Jewish page

The Black Resilience Fund recognizes that in addition to necessary systemic changes, Black Portlanders in need, especially those seriously affected by COVID-19, require financial resources.

Kol Shalom, Portland’s Community for Humanistic Judaism, has created a page called “Jewish Support for Black Lives” on the Fund’s website BlackResilienceFund.com.

“Although this action does not do much to dismantle structural racism and inequality, it is one important way for us, as Jews, to help Black people in need and to show our solidarity and support for our Black friends and neighbors,” says Kol Shalom Social Action Chair Randy Splitter. Donate on the Jewish community portal.

0Comments

Add Comment